Read the original publication at Enlace Zapatista.

From the notebook of the Cat-Dog:

Yesterday: Theory and Practice.

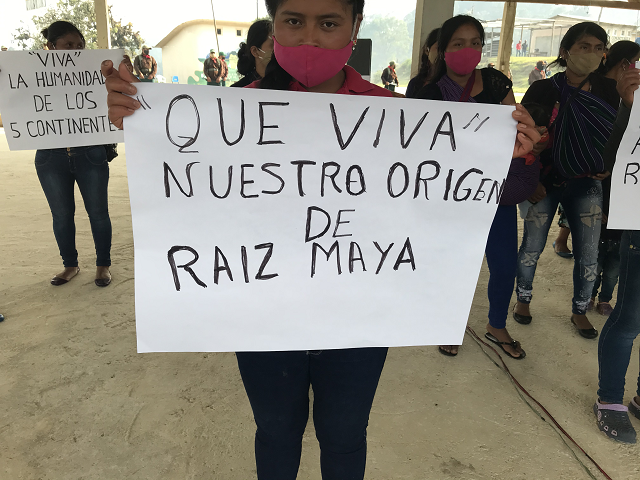

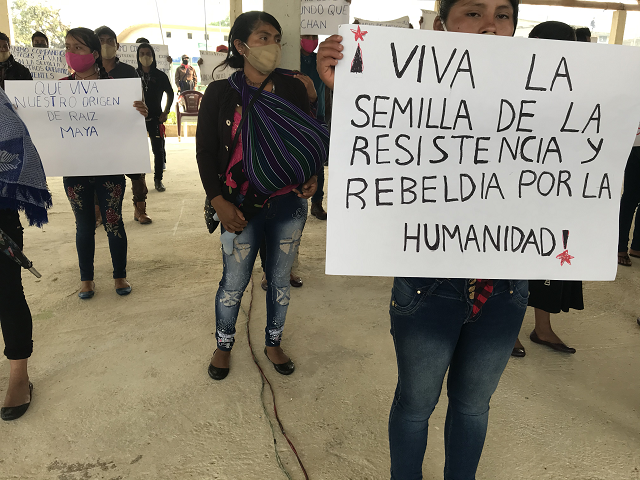

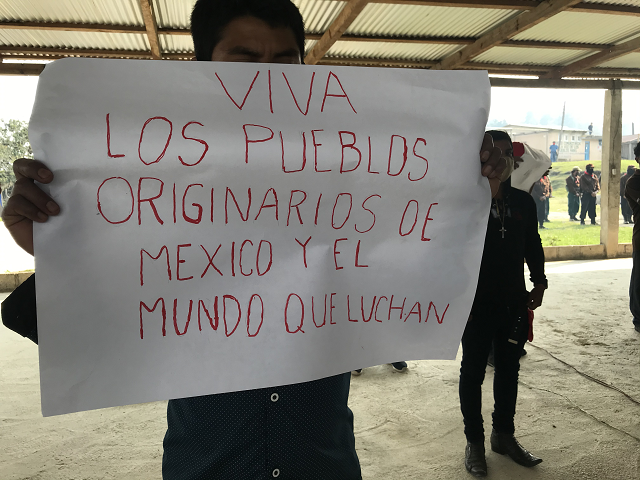

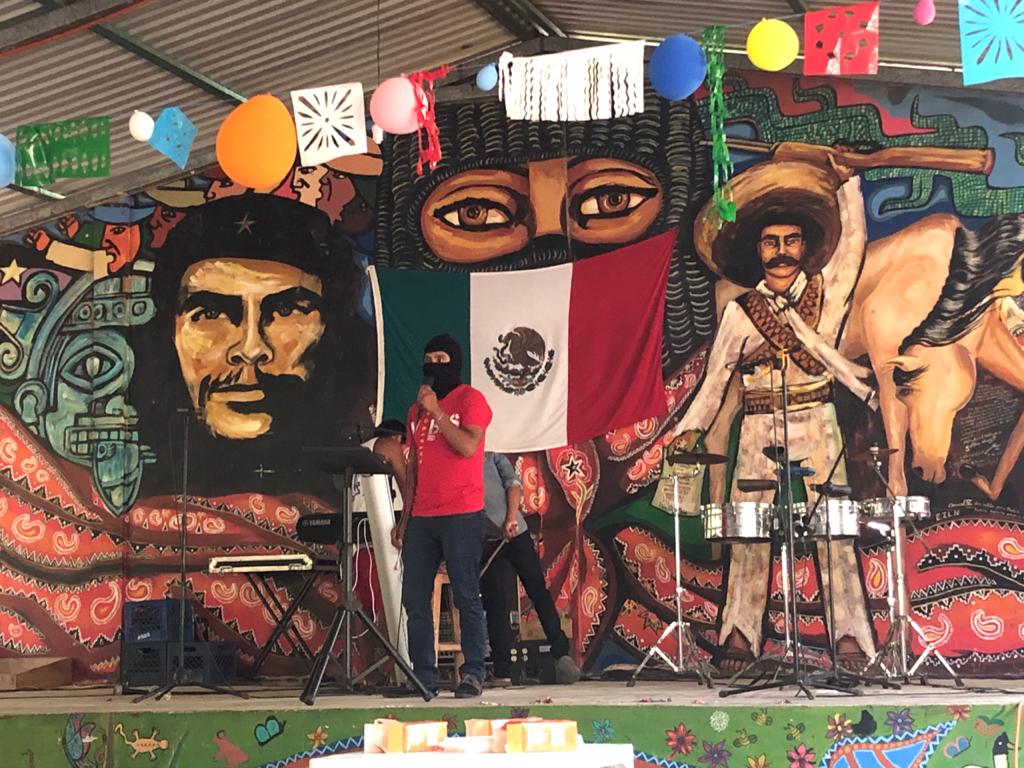

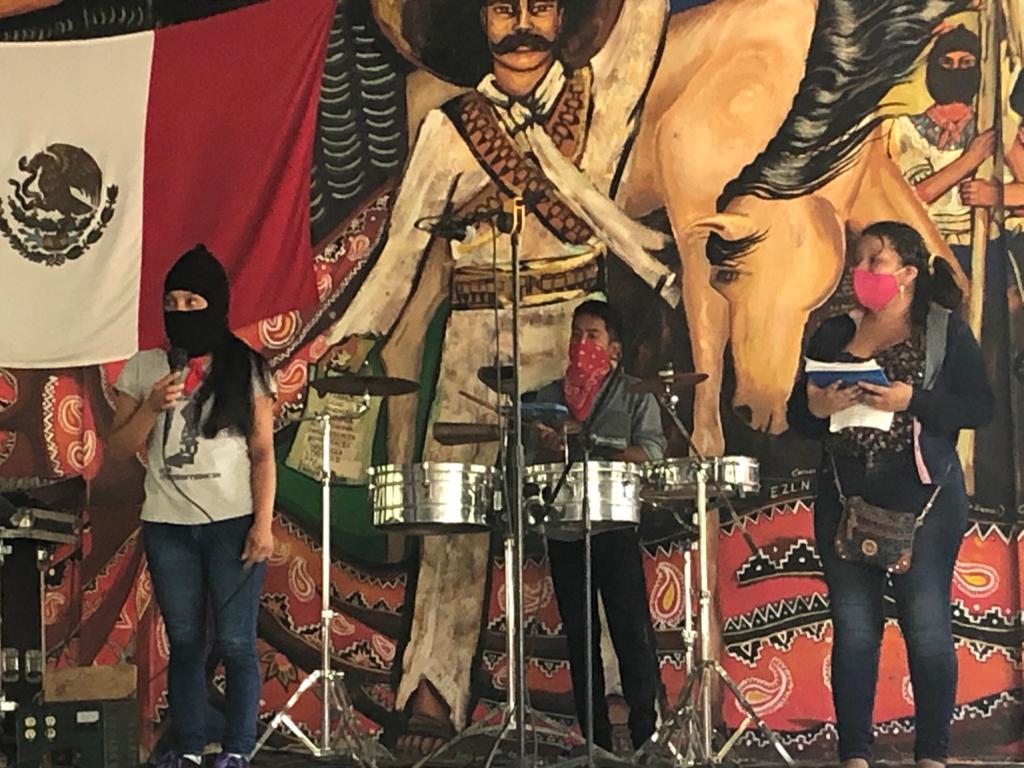

The scene: an assembly in a village of the mountains of Southeastern Mexico. It must be around July or August, likely of last year as coronavirus was taking over the planet. You can tell it’s not just any meeting, not only because of the madness that brought the assembly together, but because of the marked distance between seats and the way the fog on people’s face shields clouds the color of their face masks.

The EZLN’s political-organizational leadership is there, as are a few military leaders, although they are silent unless asked to speak on a particular topic.

There are many more people present than one might imagine. Among them they speak at least six different Mayan originary languages, but communicate with each other in Spanish, or “castilla” as we call it around here, as an intermediary language.

Many of those present are “veterans” who were part of the January 1, 1994 armed uprising and who came down from the mountains and into the cities as just one of many compañeras and compañeros. There are also “new” people, men and women who have become part of the Zapatista leadership after an extensive learning process. The majority of the new ones are women, of all ages and of various languages.

The assembly itself resembles those carried out in the Zapatista communities in its format, pace, and structure. There is a coordinator for the meeting who is responsible for indicating the previously agreed upon topics to be discussed and for giving each speaker the floor. There are no time limits on each person’s contribution, so time acquires a rhythm of its own.

Right now someone is telling a story or a history or a legend. No one is concerned with whether it is reality or fiction, but rather with the message the tale conveys.

It goes like this:

A Zapatista man is walking through a village. He’s dressed in his best finery and a new hat because, he says, he’s on his way to look for his girlfriend. The person telling the story imitates the gait and gestures he saw in one of the films shown during the first “Puy Ta Cuxlejaltic” Film Festival. The assembly laughs when he imitates the voice of Cochiloco (played by Joaquín Cosío in “El Infierno,” directed by Luis Estrada, 2010), taking off his hat to greet an imaginary woman who passes by with her imaginary mule carrying imaginary firewood. The narrator mixes Spanish with one of the Mayan languages and, without interrupting the story, those in the assembly translate for each other.

The narrator reminds them that it is the time of the fresh corn harvest, and the assembly nods in agreement. He continues:

The man in the hat runs into an acquaintance and they greet each other. “Look at you,” the acquaintance says, “I almost didn’t recognize you looking all gentlemanly and with that hat.” “I’m on my way to look for my girlfriend, “the man in the hat responds. “What’s your girlfriend’s name and where does she live?” asks the acquaintance. “Well, I don’t know,” the man in the hat answers. “What do you mean you don’t know?” The man in the hat explains, “That’s what I meant when I said I’m going to look for her, once I’ve found her then I’ll know her name and where she lives.” The acquaintance pauses to consider that profound logic and nods in understanding.

“What about you, what are you doing?” the man in the hat asks in turn. The acquaintance responds, “I’m planting corn seeds because I want some fresh sweet corn.” The man in the hat is silent for a bit, watching how the acquaintance makes holes in the gravel road with the handle of a broom. Then he speaks up, “Hey compadre, with all due respect, you’re a total idiot.” The acquaintance retorts, “What, why? I’m determined to have sweet corn and I’m giving it my best effort.”

The man in the hat sits down and lights a cigarette, passes it to his acquaintance and lights another for himself. Neither of them seem to be in a hurry, neither the man in the hat to get on his way to find his girlfriend nor the acquaintance to eat his corn. The afternoon stretches into the evening and the night starts to eat away at the light. It’s not raining yet but the sky begins to cloak itself in gray clouds and the moon creeps up behind the trees. After a long silence the man in the hat explains:

“Look compadre, I’ll try to explain. First of all, there’s the terrain. Corn is not going to grow in this gravel. It’s going to die under so much foot traffic and the roots have nowhere to take hold. There’s no doubt about it, the seed is going to die for sure. And then there’s broom handle you’re using as a hoe: a broom is a broom and a hoe is a hoe, that’s why your broom is all broken and patched together.”

He takes the hoe and examines the repairs the other man has made with tape and rope. “Look compadre, you’ve really screwed up, if I did this to my wife’s broom she’d send me to the doghouse straight away.”

He goes on, “You see compadre, the cornfield can’t be in just any old place, with just any old tools. It has a time and a place. This isn’t even the time to plant corn, this is the time of harvest. And in order to be able to harvest, you have to have worked hard in the cornfield. But the field doesn’t respond to commands like ‘I’m home woman, bring me my tortillas and my pozol,’ like you always yell at your wife. Well, that is until she started meeting with the “women that we are” collective and boom, no more yelling from you. But that’s on you. What I’m trying to tell you now is that you can’t give the earth orders; you have to talk to it, explain to it, honor it, and encourage it with stories. And the earth won’t listen just anytime, you have to know its calendar. You have to know how to count the days and nights properly, to look at the earth and the sky to know exactly when to plant the seed.”

“That’s your problem, compadre. You haven’t done any of that. You think just because you’re determined to get what you want your efforts will yield fruit. But what you need is knowledge. It’s not just a hard work and determination that gets you results; you have to choose the right terrain, the right tools, and the right time for each part of the work. That is, you need theory and practice based in knowledge, not in this nonsense you’re doing, which you really should be embarrassed about because everybody is watching and laughing.”

“That’s the thing though, they’re dumb for laughing too, because they don’t realize the foolishness you’re up to is going to affect them too. These holes you’re making are going to become puddles when it rains which will then turn into ditches across the road as deep as the wrinkles on your grandmother’s face (your grandmother, mine is already in heaven). Then the Good Government Council’s truck isn’t going to be able to get in because it’s going to get stuck, along with all the materials and goods it’s carrying, and they’ll have to carry everything on their backs, and ruin their boots and pants in the big mess of mud puddles—even worse if they’re dressed up like I am right now, and nobody will ever find a girlfriend like that. It’ll be even worse with the compañeras, compadre, because they don’t mess around. They’re going to pass right by you with a mule carrying their things and say, ‘Would you look at that, there are people dumber and more stubborn than my mule.’ And they’ll even clarify for you, ‘By the way, sir, when I say “you dumb mule,” don’t be offended, I really am talking to the animal.”

The acquaintance is taken aback: “Now wait a minute compadre, since when do we get along this badly?”

The man in the hat responds, “No, that’s not it. Take what I’m saying as advice, as orientation, not as an order. Like the late Sup used to say, ‘just do it the way I tell you, because if you don’t, then when it turns out badly I’m going to say “I hate to say I told you so but I told you so.”’ So take seriously what I’m telling you, compadre.”

“So this terrain won’t work?” the acquaintance asks, “Nor will my hoe? And it’s not even the right time to plant?”

“No, no, and no,” the man with the hat replies.

“So when is the right time?”

“Oh, it’s over for this season,” the man with the hat replies. “You’re going to have to wait for the next go, April, May, around there. And to make sure you get rain, on May 3 you need to offer the earth bread, a drink for the heat, maybe a hand-rolled cigarette, candles, and some people also offer the earth fruit and vegetables and even chicken soup. The late Sup would say, anything but squash soup, that if you give the earth squash soup it’ll get mad and yield only snakes. But I think he was lying, he just didn’t like squash.”

“When exactly is the right time?”

“Hmm, well let’s see, we’re in October now, so about 6 months from now. In April or May, it depends.”

“Shit,” the acquaintance says, “So what do I do if I want sweet corn right now?” He thinks a minute and then lights up, “I know, I’m going to ask the autonomous authorities to lend me some corn.”

The man with the hat: “And how are you going to repay the authorities?”

The acquaintance: “Well, I’ll ask the Good Government Council to lend me the corn to give to the autonomous authorities. And then I’ll borrow some corn from the Tercios Compas media team to give back to the Council, and then to pay the Tercios I’ll ask the autonomous authorities for some more corn, and in the end everyone will see that I pay my debts.”

The man with that hat scratched his head, “Shit, compadre, it’s like in that Vargas movie, you’re really turning out to be slyer than I thought*. If you’re thinking like the bad governments, you might as well be a legislator or a senator or a governor or one of those assholes. (* In Luis’ Estrada’s film La Ley De Herodes, “Herod’s Law”, another character says of protagonist Juan Vargas, ¡Ahora sí me saliste más cabrón que bonito!: You’re turning out to be slyer than I thought, you rascal!)

“What happened, compadre? I’m all about resistance and rebellion. I’ve just gotta see how to make it happen.”

The man with the hat: “All right then, I’ve got to get going or I won’t find my girlfriend. See you later compadre.”

“God bless,” the acquaintance replies, “and if you find your girlfriend, ask if her family has some corn they’d lend me, I’ll pay ‘em back later.”

The story-teller stopped and looked at the assembly: “So, which is better? Should we lend the compadre some corn or do we let him do theory and practice with knowledge?”

-*-

The assembly took a break for pozol. SupGaleano, just to be stubborn, said to Subcomandante Moisés on the way out: “That’s why I only eat popcorn,” and went off to his hut. Subcomandante Moisés retorted, “What about the hot sauce?” SupGaleano didn’t answer but veered off in another direction. “Now where you going?” SubMoy asks him. SupGaleano yells back, “I’m gonna borrow some hot sauce from the insurgentas’ store.”

I give my word. Woof-meow

The Cat-Dog, currently a stowaway on La Montaña (Well, we didn’t have enough money for everybody and plus, there’s a sign on the entrance of La Montaña that says “No cats, dogs, or schizophrenic beetles”). Mexico still, April 2021.